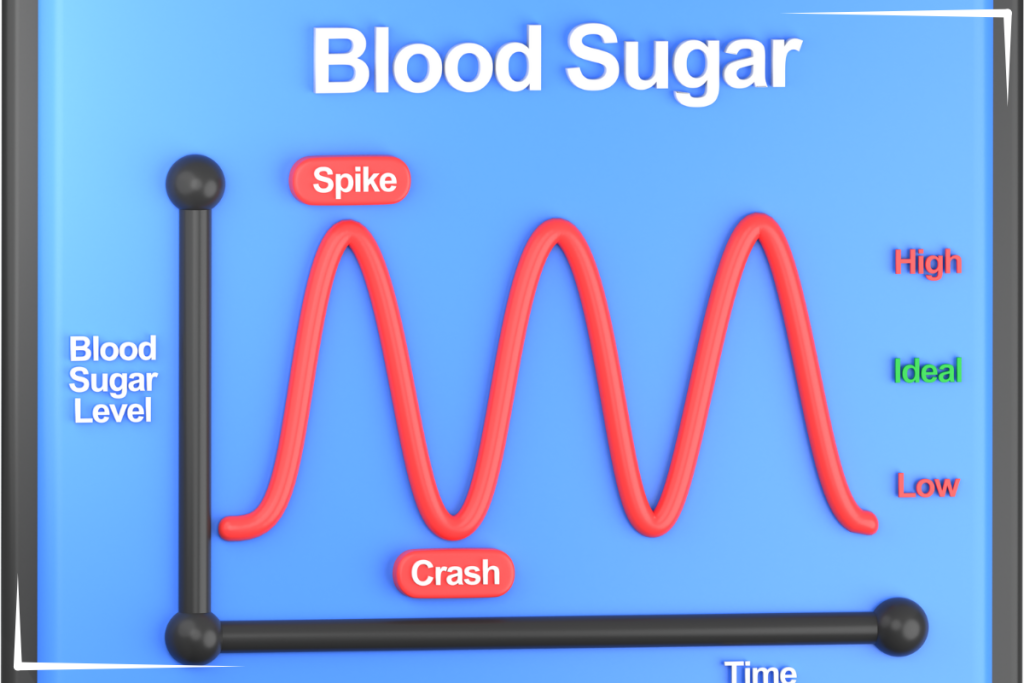

Blood sugar is not supposed to be a massive roller coaster. In a metabolically healthy body, glucose rises modestly after meals, peaks within about an hour, and then gently comes back to baseline within a few hours. Over an entire day, that pattern keeps blood sugar tightly controlled, largely bewteen about 60 mg/dL and 140 mg/dL.

The more we use continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) in people without diabetes, the clearer this pattern becomes. In other words, “normal” is not random swings between 50 and 200, for example. Normal looks surprisingly stable.

What “Normal” Looks Like in Real People on CGM

Several CGM studies in healthy, nondiabetic adults give us a concrete picture of what metabolically healthy glucose looks like. In people without diabetes, hyperglycemia occurs when glucose rises above 140 mg/dL.

In a multicenter CGM study of 153 healthy adults, Shah and colleagues found that participants spent a median of 96 percent of their day between 70 and 140 mg/dL. Time above 140 mg/dL was tiny, and time above 180 mg/dL was essentially negligible. The authors looked specifically at postmeal responses in people without diabetes. Using CGMs, they showed that the median time above 140 mg/dL was about 2 percent of the day, which works out to roughly 30 minutes total. Many individuals never went above 140 at all during the monitoring period.

So, in other reviews, healthy adults:

- Glucose typically lives between roughly 70 and 140 mg/dL

- Excursions above 140, if they happen, are brief and not the dominant pattern

That is where the practical statement comes from that a metabolically healthy person “does not go above 140 in general.” Technically, you might see a rare, short-lived spike above 140. What you should not see is repeated or prolonged time above that level.

What was also shown was that individuals who consume a low-carbohydrate diet were much less likely to experience glycemic variability.

Guidelines Quietly Agree: 140 is an Important Upper Boundary

If you look at diagnostic and guideline documents, you see the same number over and over: 140 mg/dL.

In oral glucose tolerance testing, a two hour value under 140 mg/dL is defined as normal glucose tolerance. Values between 140 and 199 mg/dL are categorized as impaired glucose tolerance, which is essentially prediabetes. Values at or above 200 mg/dL at two hours indicate diabetes.

The International Diabetes Federation guideline on postmeal glucose goes even further. After reviewing multiple CGM and meal studies, they conclude that in people with normal glucose tolerance, postmeal glucose “generally rises no higher than 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL)” and typically returns to premeal levels within two to three hours.

In other words, both real world CGM data and international guidelines converge on the same picture: for metabolically healthy people, 140 mg/dL is a practical ceiling for postmeal glucose, not a number you live above.

Why Spending Time Above 140 Matters

If brief spikes above 140 are uncommon in healthy people, the next question is: does it matter if you are often above 140 even if you are “not diabetic”?

A large meta analysis by Levitan and colleagues pooled 38 prospective studies in people without diagnosed diabetes. Those in the highest postchallenge glucose category (midpoint around 150–194 mg/dL) had a 27 percent higher risk of cardiovascular disease compared with those in the lowest category (around 69–107 mg/dL).

So risk does not suddenly start at the diabetes threshold. Cardiovascular risk climbs as glucose climbs, even in the so called nondiabetic range.

Mechanistically, there is a reason for that. Monnier and colleagues showed that acute glucose swings and postprandial excursions trigger more oxidative stress than steady chronic hyperglycemia in people with type 2 diabetes. Oxidative stress is a key driver of endothelial damage and plaque formation.

Reviews by Cavalot and others have pulled this together. Postprandial spikes are linked to:

- Endothelial dysfunction

- Increased oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling

- Progression of atherosclerotic plaque

Even though many of these studies are in people with diabetes, the biology does not suddenly switch off just below a “diagnostic” cutoff.

Hiyoshi’s review emphasizes that atherosclerosis starts early in the continuum, at the stage of postprandial hyperglycemia and impaired glucose tolerance, before fasting glucose is frankly abnormal.

Taken together, the message is that frequent or prolonged time above about 140 mg/dL is a marker of metabolic stress on the vascular system, whether or not someone has a formal diabetes diagnosis.

“Metabolically Healthy” in Practice

From a practical standpoint, you can describe a metabolically healthy glucose pattern like this (as shown by the above peer reviewed studies and data):

- Fasting glucose typically in the 70 to low 90s mg/dL range

- Modest postmeal rise, with most one to two hour readings under about 140 mg/dL

- Two hour postmeal readings reliably under 140 mg/dL

- Very little time spent above 140, and almost no time above 160–180

That pattern is exactly what we see in healthy CGM cohorts and what international guidelines implicitly recognize when they talk about normal postmeal glucose.

A person whose CGM shows frequent peaks in the 150–180 range, long plateaus above 140, or a lot of “area under the curve” in that upper range is no longer showing what the literature would call normal glucose tolerance, even if their fasting glucose or A1c are technically “normal.”

Where This Leaves You if You Use CGM

For someone using a CGM without diagnosed diabetes, 140 mg/dL is a useful line in the sand, not as a formal diagnostic cutoff but as a metabolic “tell.”

Patterns that suggest healthy control (as shown by the above data and studies):

- Most readings between about 70 and 140

- Occasional, brief peaks above 140

- Minimal total time above 140 over the day

Patterns that suggest loss of metabolic flexibility:

- Repeated peaks above 140, especially after ordinary mixed meals

- Slow returns to baseline, still elevated at two or three hours

- Significant time each day above 140, even if A1c is “fine”

Seen through that lens, “a metabolically healthy person does not go above 140 in general” is a fair translation of the evidence. The formal language would be that people with normal glucose tolerance seldom have postmeal values above 140 mg/dL and almost never spend substantial time there.

Disclaimer:

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. The content of this article, provided by Insulin Resistance Lab, is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. It is not a substitute for professional advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider with questions about medical conditions, dietary changes, or lifestyle modifications. The information provided is intended for a general audience and may not apply to individual circumstances. Do not delay or disregard medical advice based on the content of this website. Insulin Resistance Lab (Holistic Fit LLC) assumes no responsibility for errors, omissions, or outcomes resulting from the use of this information. This content is provided “as is” without guarantees of completeness, accuracy, or timeliness. The author is not a licensed medical professional. References to specific products, research, or external websites are for informational purposes only and do not constitute endorsements or recommendations. Individual results may vary. Readers are encouraged to consult updated sources and verify information as scientific knowledge evolves.

References:

Cavalot, F., Pagliarino, A., Valle, M., Di Martino, L., Bonomo, K., Massucco, P., Anfossi, G., & Trovati, M. (2011). Postprandial blood glucose predicts cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes in a 14-year follow-up: lessons from the San Luigi Gonzaga Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care, 34(10), 2237–2243. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-2414

Hiyoshi, T., Fujiwara, M., & Yao, Z. (2017). Postprandial hyperglycemia and postprandial hypertriglyceridemia in type 2 diabetes. Journal of Biomedical Research, 33(1), 1–16. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.7555/JBR.31.20160164

Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. (2023, December 18). Type 2 diabetes: Learn More – Hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes [Internet]. In NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279510/

International Diabetes Federation. (2011). Guideline for management of post-meal glucose in diabetes [PDF]. https://www.idf.org/media/uploads/2023/05/attachments-51.pdf

Jarvis, P. R. E., Cardin, J. L., Nisevich-Bede, P. M., & McCarter, J. P. (2023). Continuous glucose monitoring in a healthy population: understanding the post-prandial glycemic response in individuals without diabetes mellitus. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, 146, 155640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155640

Levitan, E. B., Song, Y., Ford, E. S., & Liu, S. (2004). Is nondiabetic hyperglycemia a risk factor for cardiovascular disease? A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(19), 2147–2155. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.19.2147

Monnier, L., Mas, E., Ginet, C., Michel, F., Villon, L., Cristol, J. P., & Colette, C. (2006). Activation of oxidative stress by acute glucose fluctuations compared with sustained chronic hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA, 295(14), 1681–1687. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.14.1681

Shah, V. N., DuBose, S. N., Li, Z., Beck, R. W., Peters, A. L., Weinstock, R. S., Kruger, D., Tansey, M., Sparling, D., Woerner, S., Vendrame, F., Bergenstal, R., Tamborlane, W. V., Watson, S. E., & Sherr, J. (2019). Continuous Glucose Monitoring Profiles in Healthy Nondiabetic Participants: A Multicenter Prospective Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 104(10), 4356–4364. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-02763